Interview questions by Adrian Grima below

L-unika kura biex ma ninbidilx f’qattiel jew nitgħallaq

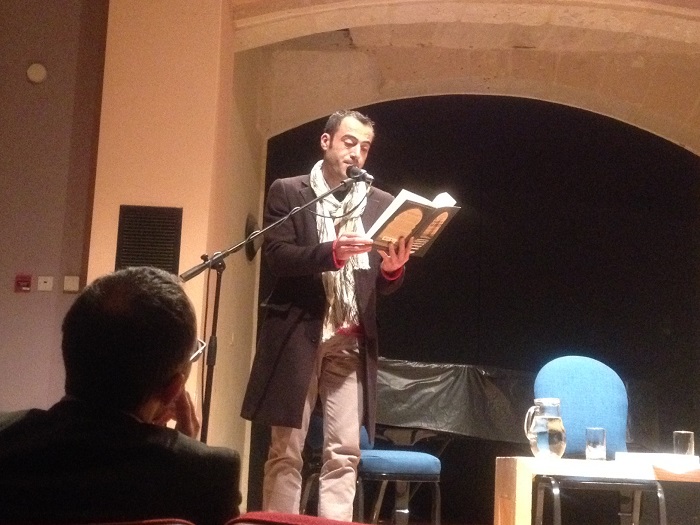

Artiklu ta’ Antonia Micallef (TVM), qari ta’ Khaled Khalifa

“Naħseb fuq il-kitba kemm fallietni u ma setgħetx tikkonsla omm waħda ta’ martri jew tgħin lill-midrub biex jirkupra, jew lil xi tfajjel taħt tinda. Imma l-kitba hija kulma jinħtieġli. L-unika kura biex ma ninbidilx f’qattiel jew nitgħallaq. Kienu reġgħu ġewni dawk l-ewwel mumenti ta’ biża li xi darba ma nkunx nista’ nikteb. Kont nitħasseb serjament u ngħid lili nnifsi li m’hemmx soluzzjoni ħlief is-suwiċidju. Issa l-idea qisha qed terġa’ tittanta. Forsi l-kitba tista’ ssalvani u tgħinni biex ngħin lil ta’ madwari. Abbli li nkun aktar qawwi u ġentili jekk jiena u nikteb ninjora l-mewt madwari. Sirt naħrab mill-ġurnalisti li jkellmuna s-sigħat twal u fl-aħħar jiktbu dak li jarawh xieraq għall-konvenjenza tal-kuxjenza tagħhom. Din il-mewt ma tikkonċernax lilhom. Faċli wisq biex tilgħab bl-aġġettivi. Min se jħaqqaqha miegħek jekk tgħid li din ir-rivoluzzjoni hija gwerra ċivili? U li aħna grupp ta’ tribujiet u razez u setet? Naturalment ħadd. Qed terġa’ taqbadni xewqa biex nidħaq bihom u bil-valuri imma m’għandi l-ebda metodu biex inwerżaq ħlief li nikteb.“

Silta b’saħħitha tradotta għall-Malti mill-awtur Malti-Palestinjan Walid Nabhan, mid-djarju tal-gwerra ‘Damascus: War Diary’ li qed jikteb l-awtur Sirjan Khalid Khalifa li jgħix f’Damasku. Id-djarju jiddokumenta l-ħajja tas-Sirjani li issa ilhom is-snin mifnijin bi gwerra.

F’attività fi tmiem il-ġimgħa li għaddiet, organizzata minn Inizjamed bl-għajnuna taċ-̇Ċentru għall-Kreattività tal-Kavallier ta’ San Ġakbu, Khalid Khalifa spjega kemm is-Sirjani jħossuhom abbandunati mill-bqija tad-dinja u kkritika lid-dinja tal-Punent li minkejja li tgħid li tħaddan id-demokrazija u tiddefendi d-drittijiet tal-bniedem, lanqas biss tipprova tifhem dak li għaddejja minnu s-Sirja.

“Bħal donnu s-Sirjani jħobbu jmutu, l-Għarab iħobbu jmutu,” qal b’ton sarkastiku Khalid Khalifa, “qisu għad-dinja tal-Punent id-demokrazija ma tgħoddx għad-dinja Għarbija u sa llum, skont il-liġi internazzjonali, dak li għaddej fis-Sirja huwa sempliċiment gwerra ċivili.”

Khalid Khalifa qed jittama li jlesti dan id-djarju sa sentejn oħra. Huwa qed jaħdem fuqu filwaqt li qed jikteb il-ħames rumanz tiegħu, xogħol li waqt li qiegħed Malta qed jaħdem fuq it-tieni abbozz tiegħu.

Khalid Khalifa bħalissa jinsab Malta wara li ħa borża ta’ studju biex jikteb. Fl-attività Albert Gatt qara silta mir-rumanz magħruf ta’ Khalifa maqlub bl-Ingliż, In Praise of Hatred. Dan huwa t-tielet xogħol ippubblikat tiegħu bl-Għarbi li ħareġ fl-2006 u kien innominat għall-Premju Internazzjonali tan-Narrattiva bil-Għarbi fl-2008. Dan ir-rumanz ġie ċċensurat fis-Sirja u ġie ppubblikat mill-ġdid fil-Libanu.

L-istorja ta’ dan ir-rumanz hija rrakkontata minn tfajla Musulmana fit-tmeninijiet fis-Sirja meta l-Aħwa Musulmani bdew iħejju rewwixta kontra r-reġim totalitarju vjolenti ta’ Hafez al Assad, missier il-president attwali tas-Sirja, Bashar al-Assad. Il-ġrajjiet li jirrakkonta r-rumanz wasslu għall-massakru li seħħ fil-belt ta’ Hama u bnadi oħrajn fl-1982.

Ghenwa Mumari, Sirjana wkoll, li tgħallem il-letteratura Għarbija fl-Università ta’ Malta u ilha bosta snin taf lill-awtur, iddeskriviet lil Khalid Khalifa bħala “mgħallem tan-narrazzjoni” li ħallas prezz għoli għax kiser is-silenzju. Fl-2012 Khalid Khalifa qala’ xebgħa kbira wara li ħa sehem fil-funeral ta’ artist ħabib tiegħu li nqatel fis-Sirja. Kienu żammewh ukoll 24 siegħa arrestat u kisrulu idu x-xellugija. Iżda bl-ironija u l-ottimiżmu tipiċi tiegħu, l-awtur kien ikkummenta li ma ġara xejn, għax hekk jew b’hekk jikteb bil-lemin.

Talking to Khaled Khalifa

An interview by Adrian Grima

St James Cavalier Centre for Creativity | Friday, 13 March 2015

1

The English edition of Khaled Khalifa’s third novel, with its Orientalist cover and its catchy title, In Praise of Hatred, may almost give the impression that the author is playing language games to attract an audience. But nothing could be further from the truth: this is a novel that delves, bravely and painstakingly, into the logic of hatred, one of the leitmotifs of this highly readable and profoundly unsettling novel. How difficult was it for you to look into the face of the deep, rationalised hatred that guides a 17 year-old veiled girl, the hatred that is lodged in the human heart?

2

“There are many people who seem to be perfectly normal, but under certain conditions, as in those that prevail in wartime, their pathological side comes to the fore, and dominates their behaviour.” . . . “If you had met any of these three men before the war, you would probably not have thought of them as particularly violent. They were not very different from other men – just three men who liked to hang out in local bars. Then the war came, and now it is over. Next thing you know, they are in prison. You read in the newspapers about what they did, andyou wonder if it is really possible. Can ordinary men behave like that? You neighbours, perhaps? Your relatives? No, it cannot be. They look so normal. You look for some obvious sign of perversity, some sign that will help you recognise them as criminals.” [Slavenka Drakulić suggests that] “the war itself turned ordinary men – a driver, a waiter and a salesman, as were the three accused – into criminals because of opportunism, fear and, not least, conviction. Hundreds of thousands had to have been convinced that they were right in what they were doing. Otherwise such vast numbers of rapes and murders simply cannot be explained – and this is even more frightening.”

3

At the beginning of your novel In Praise of Hatred, the female narrator tells us that her aunt Maryam, a very powerful character in the novel, “always insisted to me that the body is filthy and rebellious, and these words embedded themselves in me like an irrefutable truth” (16). In same passage, the young narrator tells us that another girl, the “sober and grave” Dalal, “in her black clothes,” said that “women were animated dirt.” I wonder, Khaled, whether the hatred in the unnamed narrator is the result of the alienation from her own body…

4

Khaled: you’re a great cook. What similarities and differences do you see between writing and cooking? Do they require the same kind of discipline, passion, abandonment?

5

Our friend Robin Yassin Kassab highlights the recurring motif of the embalmed butterflies. The images, the metaphors make the language “lush,” pregnant with colour and emotion, but also very poetic. What role does metaphor play when you write your prose?

6

Many Europeans talk about the Mediterranean as a shared cultural space that is based on a common history and heritage. Do you feel part of this Mediterranean cultural identity? Do you see Syria as part of a Mediterranean region? If the European Union were to propose some kind of renewed Barcelona process, an initiative to bring together the countries of the Mediterranean in a political, economic and cultural union, would you look at it as a neo-colonialist project?

7

An important chapter in the original Arabic edition of the novel In Praise of Hatred and in the Italian, French and other editions, was edited out of the English edition. Why was that? What was your reaction to this? Why is it an important chapter to you? What does it say about your idea of plot?

8

Literature is not written in a vacuum. It’s written for an audience, sometimes with a particular audience in the author’s mind. Do you agree? If you do, wouldn’t it make sense to rethink a novel in translation according to its often completely new target audience?

9

Khaled, you are often unhappy with the way the media in Europe and the United States talk about the war in Syria. One central issue is that you describe what is happening in your country as “the Syrian revolution” while the media often describes it as a civil war. You also strongly disagree with the interpretation of the war in Syria as a sectarian war, as a conflict between Sunnis, Shia, Alawis, Kurds… For you this war is about democracy, but the Europeans and the Americans continue to interpret it in ways which fit their stereotypes of the Arab world.

10

Khaled, you have chosen to remain in Damascus. We are constantly exposed to heart wrenching images coming out of a brutal war that we do not understand Can you see yourself ever writing a novel set in the war-torn Syria of today? Or is too close to home?

11

You come from Aleppo, the second city of Syria and one of the bases of the resistance. From the news we receive, Aleppo has been one of the hardest hit cities in this war. But you also have your olive trees there. what will the new Aleppo, the new Syria you dream of look like?

Thanks to Ghenwa Mumari, Clare Azzopardi, Albert Gatt, Nathalie Grima, Walid Nabhan, and Literature Across Frontiers.