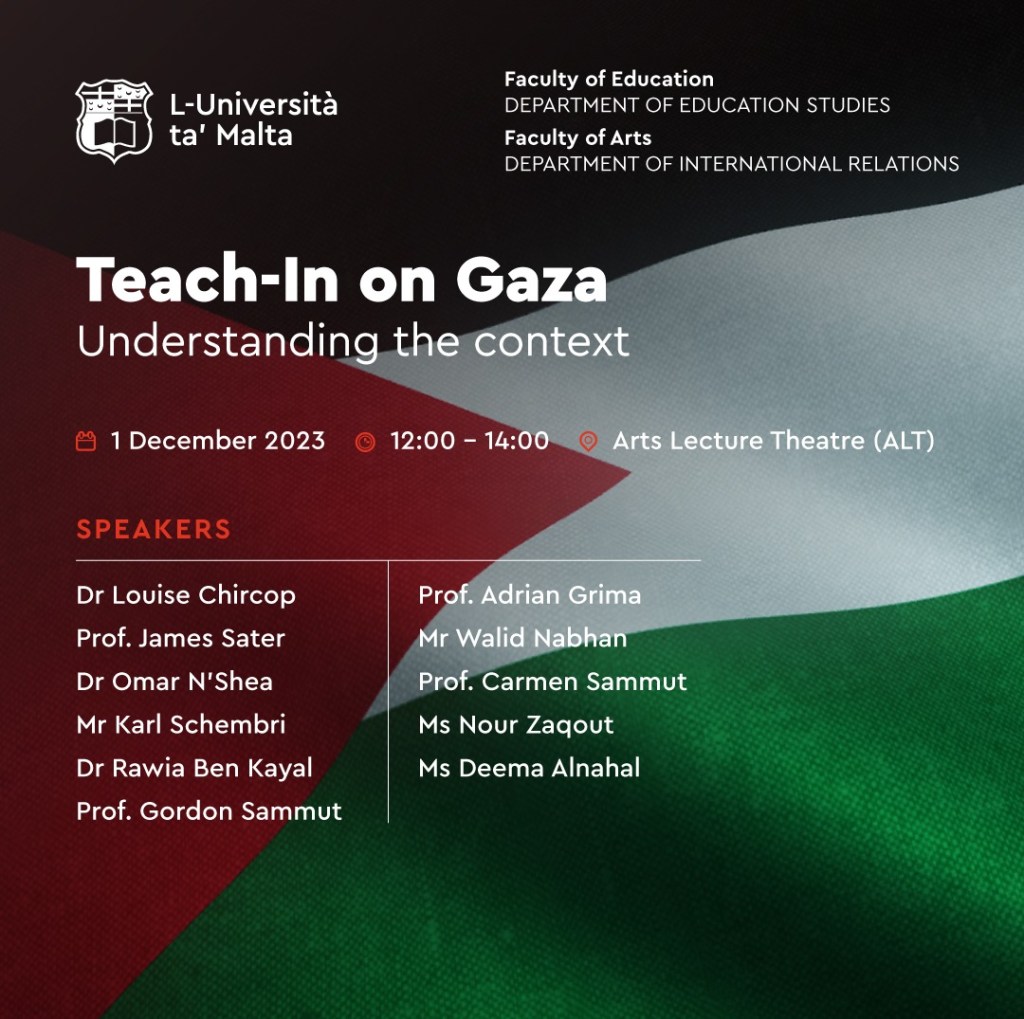

Invitation to students and staff: Teach-In on Gaza: 1 December 2023.

The ongoing Israeli-Palestinian conflict is surrounded by various narratives, making it challenging to discern accurate information. The complexity of the 75-year-old Palestinian Question adds to the difficulty of grasping the conflict’s context.

To address this, the Department of Education and the Department of International Relations are organizing a Teach-in on Gaza. This event seeks to provide a socio-political context to comprehend the situation.

A Teach-In is an educational forum that involves open discussions and presentations on a specific issue. It is designed to promote awareness, understanding, and dialogue among participants. Teach-Ins aim to engage a broad audience and to foster a collaborative learning environment

Some Context

A number of lecturers and students took part in this teach-in and these were the titles of many of their contributions: Dr Louise Chircop, Head of Department of Educational Studies: A teach-in on Gaza: the importance of learning about context in complex international issues; Professor James Sater: Can aggression heal the wounds?; Dr Omar N’Shea: The Palestinian Question and Arab identity; contributions by Ms Nour Zaqout and Ms Deema Alnahal; Dr. Rawia Ben Kayal: The political relevance of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict for the Arab world; Prof. Gordon Sammut: What does it take for the resolution of a conflict?; Mr Karl Schembri: Gaza, a first-hand experience of a humanitarian aid worker; Prof. Adrian Grima: Displacement, loss, identity, and resistance in literature; and Prof Carmen Sammut, Pro-Rector for Student and Staff Affairs and Outreach: Conclusion.

The organisers of this teach-in asked me to contribute to the session by talking about “Displacement, loss, identity, and resistance in literature.”

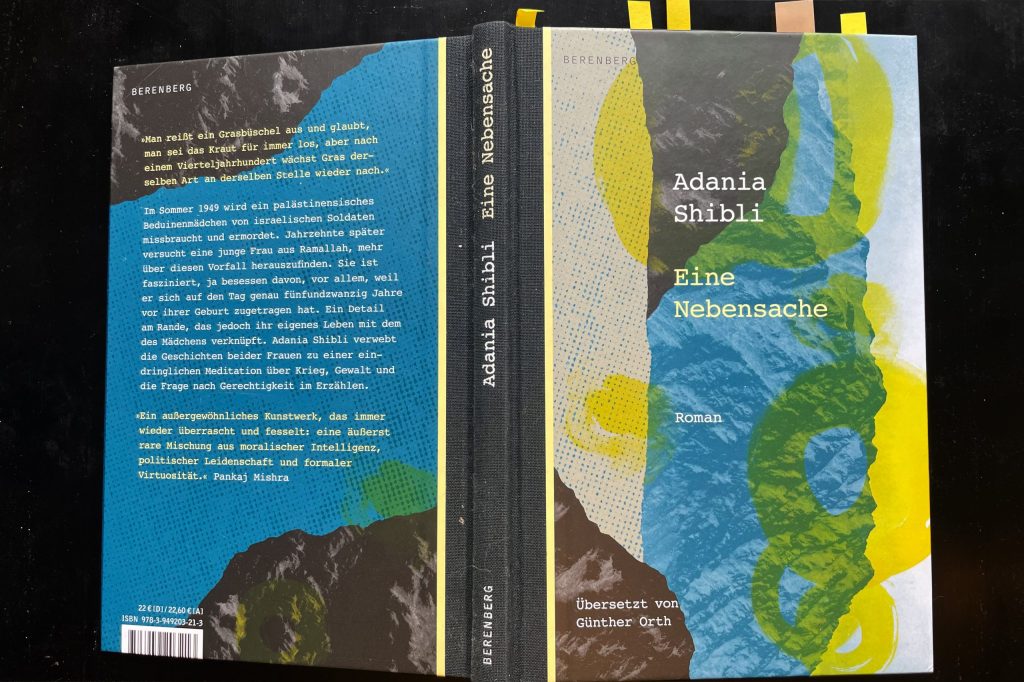

Two issues immediately came to mind: the distress caused by the constant flow of horror stories coming out of Gaza against the background of the need to reconstruct the horrible stories of what happened on October 7 when Hamas fighters attacked military posts and unarmed civilians in Israel; and the issue of Adania Shibli’s novel Minor Detail and the fact that the prize it was meant to receive at the Frankfurt Book Fair was “postponed,” or effectively cancelled. This kind of censorship is always a bad idea, and almost always has the opposite effect.

I decided to focus on the flow of images coming out of Gaza and place the issue of Adania’s prize in the wider context of the dominant narrative of Arabophobia in the “West.” After the teach-in, more stories of what Hamas fighters did on October 7 started coming out. What I said about the power of literature to bring reality home, including extreme violence, applies to what happened to many Israelis on October 7. These stories need to be told and I hope that literature finds the courage and language to tell the stories of October 7 and the ongoing carpet bombing of Gaza that followed.

First published in Arabic in 2017, Minor Detail shows how the violence of colonisation can only produce more violence. Tragically, the violence perpetrated by Hamas fighters and their allies on October 7, and the brutal collective punishment unleashed by the Israeli Occupation forces afterwards, prove the novel right.

Of course, when I gave my talk with its focus on literature, I kept in mind that my contribution was part of a more comprehensive look at the situation. So please understand that what is reproduced here is only part of a much larger whole.

Adrian Grima, December 7, 2023

Displacement, loss, identity, and resistance in literature

Adrian Grima

These past weeks have been distressing for so many of us. And we’re sitting here 1,900 km away from Gaza, in the cosiness of our extended summer, fully aware that when we can’t take it anymore, we can turn away from the horror and the humiliation and try to recover at least bits of our sanity elsewhere. I can only handle so much pain, so much wanton destruction and injustice in small doses. I can’t even start to imagine what people in Gaza are going through.

And yet, what literature does is precisely to imagine. To put itself there, in the rubble, as the screech of the cluster bombs tears through the day, through the tender flesh of love relationships, through friendship, through parenthood, through the sinews of extreme camaraderie, or rather camaraderie in extreme moments of flesh and blood.

Literature imagines. Perhaps because once it was there. Or because it has experienced something similar. Literature has this almost morbid desire to be there, in the thick of it, to smell the blood, to taste the dust, to touch the charred lives, to listen to the buildings fall like destiny, to spot the ominous drones, their introversion and pathological bouts of violence.

Literature was there. It won’t play the game of audience share. Not the best of literature. It just looks at the detail. The minor detail. Because it’s the details that tell the story, not the punditry. Not the op-eds. It’s the freeze-frame of the shell-shocked, mentally and physically rattled fourteen year boy who has spent four months in an Israeli jail. They say he was caught throwing stones at Occupation soldiers, at machine gun bearing illegal settlers rampaging through his besiiged neighbourhood.

Literature goes there, into that frame. Into that shock. Into those tired, sorry eyes, looking down a tunnel to hell. The beaten cheeks. Into the swollen lips.

So literature can be a pain. It can be a ridiculously innocuous but relentless pain. It observes. It sizes up. It tells. It goes there and it takes us there with it, into those desperate eyes. And that despair becomes our despair too. Our indignation. Because when shrapnel tears through your dignity, you bleed from the heart but you also bleed from the mind. How many pints of dignity can you lose before you lose your senses?

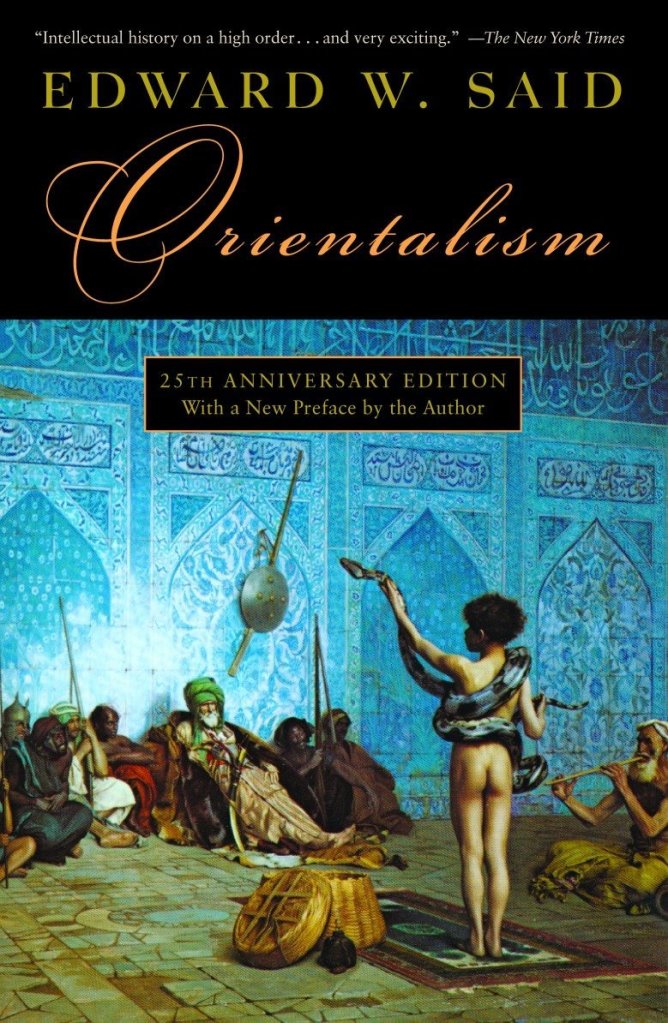

Literature can be a pain. Not because it wants to impose its narrative, but because it refuses to cower in the face of the dominant narratives. As Edward Said showed a long time ago, the so-called “West” knows all about dominant narratives, about stereotypes, about the dehumanization of the Other.

Adania Shibli’s brilliant novel Minor Detail (تفصيل ثانوي) (Tafṣīl Thānawī, translated into English by Elisabeth Jaquette in 2020) is a great example of fiction’s haunting ability to drag us through the sludge of history, to magnify the little details, to speak the unspeakable. It revisits the true story of the mass rape by Israeli soldiers in August 1949 of a young Bedouin woman. Adania takes the historically documented murder and turns it into the stuff of fiction. Fiction has this uncanny ability to make the real more real. Il-letteratura taqta’ fil-laħam il-ħaj. Literature tears into the flesh.

When Hamas’s fighters attacked Israel on October 7, leaving hundreds of dead people behind and seizing many others, one of the places they targeted was “the site of the crime” that Adania Shibli’s novel deals with and about which she spoke of the stage of the MMLF in August. The place is “now known as Kibbutz Nirim.” PEN Berlin said that this “tragic coincidence” was a “brutal reminder that this bloody conflict has been going on for 75 years” (PEN Berlin). Of course, when she wrote her brilliant novel in 2017, Adania Shibli couldn’t have known what would happen.

Her novel, which had been nominated for other prizes, “was due to be recognised at this year’s Frankfurt Book Fair (FBF) 2023 with the LiBeraturpreis award, an annual prize given to female writers from Africa, Asia, Latin America or the Arab world (Fraser). But “The ceremony was cancelled by organiser Litprom, the German literary association – which is distinct from FBF, although shares the same president Juergen Boos – due to the Israel-Gaza conflict.”

Some readers of the novel had criticized it for telling only one side of the story, the victim’s, for showing Israeli soldiers in a bad light (see AFP). Of course they had every right to do so. A novel is not a compromise text stitched together by the UN Security Council that the aggressor can simply ignore. A novel can tear into the truth like shrapnel. It cannot be ignored. One of the issues for us sitting here today in desperation is what the cancellation of that award tells us about the “West” and its dubious relation with the truth, with the Nakba, with the Occupation of Palestine since 1967.

The cancellation of the award is a reminder of how powerful literature can be, how true it can be in its fiction. But it is also a reminder of the problem the West has with the Arabophobia that Edward Said wrote about twenty years ago: in the preface to the 2003 edition of his classic exposé Orientalism, he referred to “the mobilizations of fear, hatred, disgust and resurgent self-pride and arrogance – much of it having to do with Islam and the Arabs on one side, “we” Westerners on the other” (??). In that same year, Neil Clark wrote about the “The return of Arabophobia” in the London newspaper The Guardian. “Arabophobia has been part of western culture since the Crusades,” he wrote. “For centuries the Arab has played the role of villain, seducer of our women, hustler and thief – the barbarian lurking at the gates of civilisation.” In the 20th century, “new images emerged: the fanatical terrorist, the stone-thrower, the suicide bomber.” How many minor details from literature, from this Occupation, from this latest war, does the West need to come to terms with its hypocrisies?

In the second part of Adania’s novel, the young Palestinian protagonist who goes in search of the truth about the young Bedouin woman that had been gang raped, remembers a phrase she had seen “in one of the photographs at the Nirim museum,” a museum in the kibbutz built on the ruins of the Palestinian village that had been erased: ‘Man, not the tank, shall prevail.’”

The young Palestinian woman does not dwell on the words she has just read. “I walk around the park, over the sand,” she tells us.

She’s not “listening” to the words.

She’s under no illusion.

But let’s face it, nobody is.

Post scriptum: While I was waiting for this session to start, Adania sent me this message: “Thank you, dear Adrian, for reading, for sharing with your students. Students are the good that remains in our paralysing world.”

Indeed. Students are the good that remains in our paralysing world.

References

Clark, Neil. “The return of Arabophobia.” 20 Oct 2003. The Guardian.

AFP and TOI. “Frankfurt Book Fair hit by furor after postponing prize for Palestinian author.” The Times of Israel. 16 October 2023.

Fraser, Katie. “Readers flock to Shibli’s Minor Detail.” The Bookseller. Oct 23, 2023.

PEN Berlin. “Not a minor detail: Let Adania Shibli get awarded!” PEN Berlin. 13 October 2023.

Said, Edward W. “Preface,” Orientalism. Penguin, 2003. pp. xi – xxiv.

Shibli, Adania. Minor Detail. Translated by Elisabeth Jaquette. Fitzcarraldo, 2020.

Adrian Grima, University of Malta | Friday, December 1, 2023